1.0 INTRODUCTION

Nigeria has a reputation for being a very

violent country. In 2014, it was considered to be the seventeenth most fragile

state in the world, and it was ranked 151 out of 162 countries in the Global

Peace Index, a multidimensional report on violence, security, and criminality

(Marc- Antonies, 2014). Literature on causes of violence in Nigeria identifies many factors among them selfishness,

greed, injustice, do-or-die politics, love of money, wealth, accumulation of

wealth, revolt, repression, immorality, and ignorance, etc. Violence in

Nigeria in its various forms has evolved over the decades; from the use of

traditional weapons, charms, and hamlets, violence in Nigeria has taken a sophisticated dimension. Political, electoral, religious, ethnic/tribal, cultism, and other forms of violence are dominant in Nigerian society, at varying

degrees. Each region in Nigeria has its peculiar form of violence; in northern

Nigeria, religious violence and extremist attacks are peculiar, in the

South-South, militancy is popular and like extremist attacks in northern

Nigeria, it has received global attention. In the Southeast, cultism ferocity, and robbery attacks are common forms of violence, while in the Southwest,

political violence and thuggery are intrinsic. However, this doesn’t mean other

forms of violence such as gender-based violence (rape, abuse, intimidation), and tribal clashes among others still exist across the regions of Nigeria (Rotimi,

2019).

2.0 DISCUSSION

Accordance to the World Health Organization’s Violence Prevention Alliance1,

‘violence’ is the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual,

against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either

result in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death,

psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation. This includes neglect,

physical, sexual, and psychological violence, and can be interpersonal (towards

a family member, partner, acquaintance, or stranger), self-directed, or

committed by larger groups such as nation-states and terrorist organizations (WHO 2017c).

Addressing violence is not a

single-agency issue, as it is the culmination of many different issues. It is

only by pursuing a strategic, coordinated approach involving a range of

agencies, including partnerships between statutory and voluntary organizations,

that violent crime can be effectively addressed. Therefore, it is imperative to

look into the topic of the public health approach to violence prevention in Nigeria.

The World Health Organization (WHO)

(2017a) defines a public health approach to reducing violence as one that: ‘Seeks to improve the health and safety of all

individuals by addressing underlying risk factors that increase the likelihood

that an individual will become a victim or perpetrator of violence. By definition,

public health aims to provide the maximum benefit for the largest number of

people. Programs for primary prevention of violence based on the public

health approach are designed to expose a broad segment of a population to

prevention measures and to reduce and prevent violence at a population level.’

Public health approaches can be identified by

the following characteristics:

• defining and monitoring the

problem

• identifying causes of the

problem, the factors that increase or decrease the risk of violence, and the

factors that could be modified through interventions

• designing, implementing, and

evaluating interventions to find out what works

• implementing effective and

promising interventions on a wider scale, while continuing to monitor their

effects, impact, and cost-effectiveness (WHO, 2017a).

According

to Anikweze( 1998), the

perspective of public health on the Violence

Prevention Alliance revolves around three theoretical models: the typology of

violence, the public health approach, and the ecological framework. These models

guide understanding, research, and action for violence prevention. The typology

is a tool to help organize thinking about the types of violence and how violence occurs. The public health approach offers practitioners, policymakers, and researchers a stepwise guide that can be applied to planning

programs, policies, and investigations. Finally, the ecological framework

bridges these two models, giving a structure to understanding the contexts

within which violence occurs and the interactions between risk factors in each

of these contexts and between them. The ecological framework shows where and

how to apply the public health approach and is useful for categorizing planned

or existing interventions to help understand the mechanisms by which they might

be working, John et al (2001).

2.1

Public health approach to violence?

Public health approaches work

by providing a framework that seeks to understand what causes violence and

respond with interventions to prevent or reduce violence, at the population

level, informed by the best available evidence. Public health approaches

undertake robust research and analysis to identify risk and protective factors

that are associated with violence. Definitions of risk and protective factors

are presented below.

• Risk factors are those which can usefully predict an increased likelihood of violence.

For example, communities with high levels of unemployment may be at higher risk

of experiencing increased levels of violence.

• Protective factors are factors that reduce the likelihood of violence. For example,

communities with low levels of unemployment may be at less risk of experiencing

high levels of violence.

2.2 Effectiveness of public

health approaches in reducing violence?

The public health approach

outlined above provides a useful framework for taking an evidenced-led

approach to violence reduction. As well as approaches to generating evidence

concerning the causes of violence in populations, a public health approach can

also deploy a range of interventions aimed at reducing violence at the

population level (CDC,2006).

2.3 Interventions aimed at

supporting parents and families

• The Family Nurse Partnership

• Incredible Years of Preschool

• Family Foundations

• Triple P

• Empowering Parents

Empowering Communities

Developing life

skills in children and young people

• The Good Behaviour Game

• Incredible Years Child

Training (Dinosaur School)

• Incredible Years of Teacher

Classroom Management

• Promoting Alternative

Thinking Strategies (PATHS)

• Let’s Play in Tandem

Working with high-risk

youth and gangs/community interventions

• Community Initiative to

Reduce Violence (CIRV)

Identification, care, and

support

• Identification and referral

to improve safety (IRIS)

Multi-component

interventions

• Multisystemic therapy Obi

(2007).

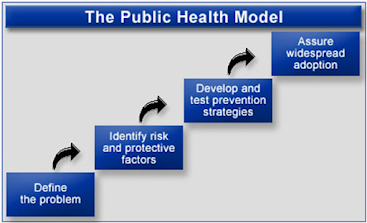

2.3 Steps of the public health approach

Adapted from CDC

(2015)

When considering public health

approaches and the implementation of interventions to reduce violence, we

consider the following:

1. Surveillance. What is

the problem?

• Define the issue. This includes conducting a robust needs assessment concerning violence,

including types of violence as well as gaining a clear understanding of risk

and protective factors that can be targeted in individuals, families,

communities, and populations to address and reduce violence at a population

level.

2. Identify risk and protective

factors. What are the causes?

• Understand the causes of violence.

This includes taking an

evidence-led approach to understanding which risk and/or protective factors

cause the violence issue and how they interplay. Through achieving this understanding,

local areas are more likely to be successful in implementing public health

interventions that effectively moderate and address risk factors and strengthen

protective factors, ultimately reducing violence at a population level.

3. Develop and identify

interventions. What works for whom?

• Develop an anti-violence or reducing violence strategy. Critically, this strategy should respond to an identified need in the population under consideration and focus on addressing

the causes of violence. The strategy should be developed and agreed upon between

stakeholders and be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Timebound.

The strategy should link to the wider strategic and policy context and include

collaborative and co-productive development with local partners, including the

local community, which should ensure local ownership of the strategy and help

to ensure that it is implemented as intended.

• Commission and fund evidence-based interventions that

have been shown to reduce violence. Where possible, local areas should consider commissioning and funding

evidence-based interventions that have been shown to reduce violence.

• Don’t be afraid to innovate.

If there are no off-the-shelf’

evidence-based interventions available, then interventions should be developed

based on existing evidence for what works in modifying risk and

protective factors for the particular kinds of violence problem that the area

is aiming to address.

4. Implementation. Scaling

up effective programs and interventions

• Implement interventions ensuring that fidelity is maintained in line with what has been demonstrated to work.

Model fidelity means ensuring

that the model implemented stays loyal and is delivered as close to the

original model as possible. This requires careful consideration when taking

into account the context into which the intervention is being rolled out. Not

ensuring model fidelity is one of the key reasons why the implementation of

interventions that have been evidenced to work in one area do not work in

another.

• The implementation of interventions takes time to embed

in practice and to achieve outcomes.

Local decision-makers need to

provide sufficient time for programs and interventions to impact desired

outcomes. It can sometimes take over five years for programs to achieve

outcomes.

• Evaluate and monitor the success of public health

interventions.

This review shows that there

is still work to be done in developing and evaluating public health

interventions aimed at reducing violence at a population level. Although

resources are often tight, you should aim to contribute to the evidence base by

ensuring robust evaluation of public health interventions that are commissioned

and funded. Robust evaluation can save money by clearly identifying models and

practices that work, but also showing what does not work. Knowing this can save

money and use scarce resources more effectively in the long term.

Public health interventions

operate by modifying the risk factors that make an individual, family, or

community vulnerable to violence (as victims, perpetrators, or both) and by

promoting protective factors.

2.4 The ecological framework

The ecological

framework is based on evidence that no single factor can explain why some

people or groups are at higher risk of interpersonal violence, while others are

more protected from it. This framework views interpersonal violence as the

outcome of interaction among many factors at four levels—the individual, the

relationship, the community, and the societal.

- At

the individual level, personal history and

biological factors influence how individuals behave and increase their

likelihood of becoming a victim or a perpetrator of violence. Among these

factors are being a victim of child maltreatment, psychological or

personality disorders, alcohol and/or substance abuse, and a history of

behaving aggressively or having experienced abuse.

- Personal relationships such

as family, friends, intimate partners, and peers may influence the risks of

becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence. For example, having violent

friends may influence whether a young person engages in or becomes a

victim of violence.

- Community contexts in which social relationships occur, such as

schools, neighborhoods, and workplaces, also influence violence. Risk

factors here may include the level of unemployment, population density,

mobility, and the existence of a local drug or gun trade.

- Societal factors influence whether violence is encouraged or

inhibited. These include economic and social policies that maintain

socioeconomic inequalities between people, the availability of weapons, social and cultural norms such as those around male dominance over

women, parental dominance over children, and cultural norms that endorse

violence as an acceptable method to resolve conflicts.

The ecological

framework treats the interaction between factors at different levels with

equal importance to the influence of factors within a single level. For

example, longitudinal studies suggest that complications associated with

pregnancy and delivery, perhaps because they lead to neurological damage and

psychological or personality disorder, seem to predict violence in youth and

young adulthood mainly when they occur in combination with other problems

within the family, such as poor parenting practices. The ecological framework

helps explain the result—violence later in life—as the interaction of an individual

risk factor, the consequences of complications during birth, and a related risk factor, the experience of poor parenting. This framework is also useful to

identify and cluster intervention strategies based on the ecological level in

which they act. For example, home visitation interventions act at the

relationship level to strengthen the bond between parent and child by

supporting positive parenting practices.

The ecological framework:

examples of risk factors at each level

Adapted from WHO

(2017b)

2.5 Types of

public health interventions for violence prevention/reduction

Central to an effective public

health approach to reducing violence is the implementation of interventions

that successfully address risk and protective factors in individuals, families,

communities, and populations to reduce violence at a community and/or population

level.

However, definitions varied

and there was no clear consensus or definition as to what constitutes a public

health intervention to reduce violence, apart from that it should reduce

violence at the community and/or population level.

Conaglen and Gallimore (2014)

describe violence prevention interventions as operating on various levels

(primary, secondary or tertiary) and define interventions to address violence

as universal, selected, or indicated.

2.6 Levels of violence prevention

Adapted from WHO

(2019)

Primary – preventing violence before it happens, i.e., reducing the number of new cases of violence in the population.

Secondary – immediate responses to incidents of violence to

decrease prevalence after early signs of the problem, i.e. to reduce the

prevalence of violence in the population.

Tertiary – to intervene once the violence problem is

evident and causing harm.

Types of

intervention to address violence

Universal – aimed at a general population

Targeted

selected – targeted at those more at

risk

Targeted

indicated – targeted at those who use

violence

While the WHO, Bellis et al.

(2012) and others provide clear definitions of public health approaches, there

is less clarity in the literature about what kinds of interventions fall within

the scope of a public health approach. This is complicated by the fact that the

position of an intervention in the matrix (i.e., primary, secondary, tertiary,

universal, targeted selected, targeted indicated) is rarely explicit. However,

public health interventions, like public health approaches should seek to

reduce violence at a community and/or population level.

3.0 CONCLUSION

The preceding discussions have shown that violence is an ill wind of

social phenomenon, which blows no one any good. In its aftermath both its

perpetrators and victims are losers. As a way out of the mess, Nigerian policymakers should imbibe the public health

approach while working on violence prevention and reduction in the country.

References

AfrolNews (2007) Half

of Nigeria’s Women experience domestic violence. retrieved May 22, 2008,, from

http://www.afro.com/ articles/16471

Anikweze C. M. (1998)

Threats to adolescent well being. In Orji S.A and C. M. Anikweze (eds.)

Adolescent Psychology. 109 – 117.

BBC News Education (2003) Violence at Home

hits children’s IQ. Retrieved May 2008 from http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/

education/2981312.stm.

Catalano, R; Lind, S, Rosenblatt, A and R

Novaco (2003) Research into the Economic antecedents of Violence. American

Journal of Community psychology.

CDC (2006) Intimate Partner Violence – fact

sheet. Retrieved Oct. 2008

Dahlberg, L. L. and E. G Krug (2002) Violence

– a global public health problem. In King E, Dahlbergl, Meray J. A and A. B

Zwi, Lozano R (eds.)

World Report on violence and health. Geneva.

Switzerland: WHO, 1-56. Dobson (1984) Dare to Discipline. Weston Illinois:

Tyndale House Publishing

Obi, S. N., and B.C.

Ozumba (2007) Factors associated with domestic violence in South-East Nigeria.

Journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 27. (1) 75 – 78. Prevalence of Domestic

Violence in Nigeria: Implications for Counselling

Richie, O. N. 8 Straus, M. (1994) Beating the

devil out of them; Corporal Punishment in American families. New York.

Lexington Books

UNICEF (2001) Children

and Women’s rights in Nigeria: A wake-up call situation assessment and

analysis. Edited by Hodge. Abuja: National Population Commission and UNICEF.

UNICEF (2005) Violence at home (archive)

Voices of Youth Forum. Retrieved Oct. 2008

Dahlberg

LL, Krug EG. Violence: a global public health problem. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL,

Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, eds.

World Report on Violence and Health.

Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002:1-21.